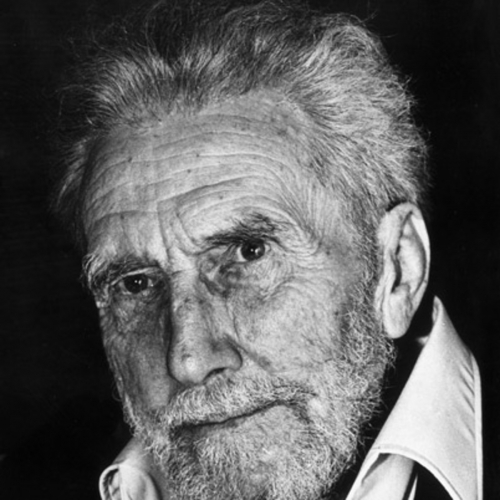

Jean Parvulesco

Cantos pisanos

Fragments, notes de mes carnets du Bunker Palace Hôtel

« Tout ne doit-il pas se retrouver à la fin du Manvantara, pour servir de point de départ à l'élaboration du cycle futur ? »

René Guénon

« Et si tu trouves des traits gravés dans les pierres, sous la poussière des routes, foulées par des pas innombrables - nul ne sait plus que ce sont des Runes Sacrées, elles avaient jadis grande signifiance et maintenant tous ont désappris le chant qui donnait à ces signes une vivante puissance magique - alors ne montre pas tes larmes !

Recueille ces trouvailles et consacre-les silencieusement au Royaume des Mères. Là ce qui fut abandonné peut se reposer dans l'attente d'une forme nouvelle, jusqu'au jour où une autre jeunesse en rêve de nouveau.

Cacher et conserver, c'est aux sombres époques de renversement l'unique office sacré »

Hans Carossa

« Où sont les douces pelouses avec le clair ruisseau, entre elles, les séparant ».

Ezra Pound, Canto LXXXIV

11

Comme nous approchons des temps de la conclusion manvantarique du grand cycle dont nous assumons l' ultime fond de lie tout en assurant, aussi, les premières relevailles, bien des choses qui s'eussent voulues cachées jusqu'à la fin se laissent à présent surprendre dans la transparence à la fois tragique et fragilisante d'une mise-à-nu qui, ne fût-ce que symboliquement, les apparente, soudain, aux prestations liturgiques de la mort, aux obscures ordalies de ce passage des êtres et des choses par le vide de leur autodissolution initiatique où tout finit et tout recommence et où leur part d'éternité leur est instituée intacte, et plus limpide, terrible et mystérieuse chrysopée philosophique dont parlent à couvert les textes hermétiques occidentaux et que la grande Savitri Dêvi rapprochait, précisément, de ce passage de l'or par l'épreuve royale de la fournaise, the gold in the furnace disait-elle, qu'aura été aussi, en dernière analyse, la fin historique d'une civilisation brisée, anéantie par la trahison intérieure, par les flammes et par le feu mais, de par cela même, vouée imprescriptiblement à la spirale de son assomption transhistorique finale.

Ainsi en est-il, aujourd'hui, de l'aventure spirituelle de l'exil. A l'heure où des êtres et les choses risquent d'avoir à se laisser surprendre, d'un instant à l'autre, dans leur plus extrême nudité intérieure, l'exil n'est plus une nostalgie, et bien moins encore la péripétie d'un quelconque déchirement dramatique de la vie, aussi atroce fût-il ce déchirement et périclitée cette vie, mais la marque brûlante et l'engagement accepté d'une prédestination secrète, puisque l'exil représente et n'en finit plus d'établir les états d'une situation ontologique de limite, et de limite ultime, la condition même d'un état de rupture ontologique totale: c'est l'exil, la conscience de l'exil et la conscience de cette conscience elle-même qui fondent la spacialité lumineuse et vide, l'immaculée conception de tout recommencement poétique de soi-même et du monde, de tout retour existentiel et historique à l'être.

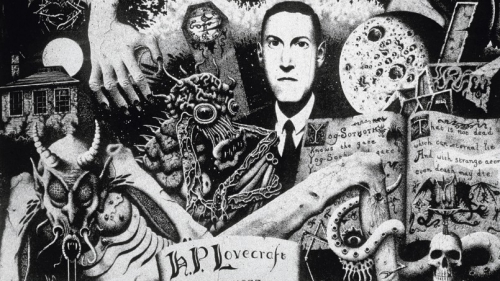

Car c'est dans la mesure même où elle implique et donne refuge en elle, ne fût-ce que d'une manière figurative, liturgique, à l'exil ontologique de l'être perdu dans les nuits de son propre obscurcissement, que toute expérience existentielle de l'exil annonce l'avènement de l'être avenir, l'imminence à la fois solaire et tragique de l'avènement occulte de ce qui vient, voire de celui qui vient, avènement si prophétiquement invoqué par Hans Carossa dans son Geheimnisse des reifen Lebens, où le regard transcendantal du visionnaire entrevoit les temps du salut er de la délivrance à venir par-delà les résurgence historiques actuelle de l'Anti-Règne des puissances négatives au service du « chaos intérieur » ou, comme le disait un autre grand américain réduit à l'exil, et même à l'exil intérieur, P.H Lovecraft, le « Chaos rampant ».

12

Une autre chose aussi me semble absolument certaine: c'est qu'il n'y a pas, il n'y a jamais eu et il n'y aura jamais une vraie grande poésie, une grand pensée ni une grande littérature, une grande culture de droite.

Toute vraie poésie, vivante et agissante, orphiquement opératoire, donneuse de vie et de souffle vivifiant, toute grande pensée salvatrice, toute grande littérature, toute culture grande, totale, véritablement et profondément grande, seront, toujours, ne sont ni ne puissent être absolument ne pas être qu'une poésie, une pensée, une littérature, une culture d'extrême-droite.

C'est que, depuis les architecture cyclopéennes des saisons supra-historiques médiumniquement entrevues par P.H Lovecraft jusqu’aux créations métacosmiques d'un Constantin Brancusi, depuis Empédocle jusqu'à Heidegger et depuis Virgile et Dante jusqu'à Hölderlin, Ezra Pound et Joyce, le dire total, le dire totalitaire du dire a eu partie abyssalement liée avec l'être, alors que les tenant avoués ou occultes du non-être, les partisans des puissances de la négation et du chaos pré-ontologique se trouvent infailliblement empêchés d'avoir recours à la parole vivante, et cette infaillible interdiction étant, en elle-même, ce par quoi s'affirme et se donne à dévoiler, se donne à reconnaître la présence même de l'être, sa présence vivante, la présence réelle de l'être dans l'être même de son unique parole de vie. L'être est, le non-être n'est pas.

Si seules les réappropriations de l'être, fussent-elles nocturnes, et même nocturnissimes, données en attente, en absence, en immémoire agissante, parviennent jusqu'aux fondations de leur propre remise en état impériale, régnante et rayonnante à nu dans leur propre dire de soi-même, c'est que tout projet du non-être est exclu d'avance, irrémédiablement, du domaine de la parole et de la vérité de l'être, qui, seule vivante, est seule à dénominer, à élucider, à délivrer ce qui n'attend que de l'être.

Dans les saisons de l'occultation métacosmique de l'être, le seul jugement est celui de la poésie, et peut-être aussi le seul salut, et la seule délivrance. Tout est perdu, mais non le chant de la détresse de qui, dans la perdition, se dédouble par le chant de détresse de sa perdition.

13

La poésie donc, état à la fois ultime et originel, ne parvient à fonder l'histoire engagée dans ses recommencements ni, dans les étapes nocturnes de son devenir, à en assumer et sauver le tout dernier souffle, que si elle-même, la poésie, tournée vers les développements voilés de sa propre essence, y instruit et proclame le mystère virginal de ses propres fondations mises à nu et rien d'autre, fondations vivantes et agissantes de la poésie en tant de poésie dont l'unique espace d'intériorité et d'influence souterraine est, depuis toujours, l'espace à la fois fermé et ouvert de l'exil. Espace fermé à jamais sur lui-même, mais ouvert indéfiniment à tout ce qui participe de ce clair-obscur, de cette désespérance lucide de la conscience séparée pour laquelle le jour se veut nuit et la nuit est comme le jour, espace entre chien et loup où naissent et viennent s'affirmer, révolutionnairement, tous les pouvoirs nouveaux. « Nous autres, fils du clair-obscur, écrivait Hans Carossa, nous servons aussi fidèlement la nuit que le jour. »

Située dans la clair-obscur ontologique où il lui est demandé de servir également la nuit et le jour, l'être et le non-être, l'histoire dans ses périodes d'ensoleillement et dans ses détours crépusculaires, la poésie se maintient néanmoins au-delà du jour et au-delà de la nuit, au-delà de l'être et du non-être, au-delà des clartés et des ténèbres de l'histoire dans un endroit originellement hors d'atteinte qui est, précisément, le lieu même de ce qui fait qu'au-delà de l'histoire il y ait une transitoire, que le jour et la nuit, que l'être et le non-être, perpétuellement en devenir, se trouvent perpétuellement appelés à se dépasser suivant la spirale ascendante de ce devenir lui-même, qui apparaît comme étant, en lui-même, occultement, un troisième état ontologique. J'entends l'état de clair-obscur où seule règne la poésie, règne totalitaire de ce qui se refuse à toute division, à toute séparation de cet Empire de la Totalité où se laisse approcher le Troisième Etat de l'être, l'Abgründ de Meister Eckhart, le mystérieux Anschau de Wolfram Von Eschenbach.

Cependant, l'inspiration poétique - m'aventurerais-je à dire la dictée poétique - ne parvient plus, ici, ou plutôt à partir d'ici, à se conceptualiser sans dommages, sans les infiltrations obstruantes, les pièges et les empêchements de sa propre résistance intérieure à un dire de soi-même de plus en plus périclitant, dangereux pour ses derniers retranchements, et j'insiste encore, comme déjà sur les lisières de l'équivoque, du mal dit, ce n'est que pour assurer les lieux de convenance où vont avoir à se porter toutes nos interventions au sujet des Cantos Pisanos.

Car le secret des Cantos Pisanos est celui du dépassement de l'histoire immédiate par l'action poétique, ou plutôt par l'Action Directe de la Poésie Absolue, le secret, donc, de la reconstitution indéfinie de l’Anschau impérial de la poésie en action sur les étendues de ruines chaotiques où n'en finit plus de ne pas se faire ou de se défaire avant de se refaire le Troisième Empire de la Fin, jusqu'à ce que l'heure vienne.

14

Ainsi comprendra-t-on que ce n'est pas la poésie qui est en exil, et bien moins encore en exil par rapport au monde, à l'histoire, mais que ce sont l'histoire dans sa totalité et le monde lui-même qui sont en exil par rapport à la poésie.

Tout exil est poésie et toute poésie exil, mais l'exil que l'on vit dans la poésie n'est plus l'exil, ni obscurcissement, ni désespérance de l'exil quand il se dévoile, au détour d'une soudaine fulguration, l'espace d'ensoleillement et de puissance totalitaire où se dressent vertigineusement dans l'air limpide du chant les remparts étincelants du Troisième Etat de l'être, la fulguration préontologique de la Turning Island qui hante le grand rêve celtique, la mystérieuse Wagadu invoquée par Ezra Pound, ombre de l'ombre de l'Atlantide engloutie par les abîmes, et de toutes les Atlantides, y inclus les plus récentes. Regarde ! Regarde-moi, avant que je retourne dans la nuit. Là où rayonne la Tête de Mort, revivront à nouveau les soldats, retourneront les étendards, Cantos LXXII.

15

Après la clôture du cycle indo-germanique des Védas Sacrés, dernière réminiscence, dernière anamnesis voilée des temps du chant hyperboréen antérieur, commencent les chemin crépusculaires du grand cycle historique actuel, qui est, originellement, une fin de cycle, une longue entrée dans la nuit et dans les ténèbres de l'exil ontologique d'une histoire, d'une civilisation, d'une race appelées à traverser l'épreuve royale du feu qui anéantit tout, l'épreuve du gold in the furnace. Aussi le devenir de ce cycle s'identifie-t-il avec l'histoire même de l'Occident, et les quatre étapes de son entrée dans la nuit reproduisent les quatre étapes fondamentales de sa poésie qui établit et renouvelle, d'une manière à chaque fois moins lumineuse, moins transparente, la situation en devenir de son exil d'origine, jusqu'à la fin. Mais, ainsi que l'écrivait Hölderlin en conclusion à l'un de ses plus grands hymnes, « ce qui demeure toutefois, c'est ce que fondent les poètes ».

16

Chaque grand cycle historique occidental se reconnaît dans le chant de sa propre poésie fondationnelle. Virgile, Dante, Hölderlin, Ezra Pound: la constellation suprême de la poésie occidentale dans son devenir transhistorique propre, reconstitue, à travers le chant continuel mais de plus en plus désensoleillé de ses témoins prédestinés, de ses témoins chaque fois sacrifiés, immolés par le feu de la poésie absolue, par le Brasier Ardent de la continuité du chant occidental, la figure héraldique du désastre historique l'Occident, l'exil transcendantal dont se nourrissent souterrainement les aliénations et la mise-en-ténèbres de son espace de probation tragique, de son sang et de sa conscience prisonniers d'une dialectique d'obscurcissement désormais et depuis si longtemps déjà sans issue ni salut.

La poésie, dialectique agissante de la transhistoire à travers laquelle elle naît et se renouvelle indéfiniment dans l'histoire, apparaît ainsi comme la politique occulte d'un cycle transhistorique, comme la métapolitique en action de son propre devenir transcendantal.

Ce que Virgile, Dante, Hölderlin et Ezra Pound ont invoqué et fait naître dans leur chant ininterrompu, c'est le lamento hyperboréen, l'anamnesis ensoleillante d'une race spirituelle qui ne peut pas ne pas se souvenir , et jusqu'au plus interdit de son oubli préventionnel - et quel oubli profond est à présent son grand oubli, son refuge, son dernier refuge, son sommeil dogmatique et son Kiffhauser mental enseveli sous les cendres - qui ne peut pas souvenir, dis-je, des temps historiques, des saisons métahistoriques où l'espace de liberté ontologique réelle n'était pas encore exclue de sa propre histoire, de son propre espace d'être, et jusque de son propre sang et de sa propre conscience d'elle-même.

17

A mesure, cependant, que la grand aliénation occidental de la fin avance dans l'histoire et se développe négativement, son mystère originel, et même, en quelque sorte, sa raison agissante, deviennent de plus en plus patent, de plus en plus manifeste: la poésie d'Ezra Pound, qui en rend compte tout en essayant de le dépasser, finit, dans ses Cantos Pisanos, par faire, de ce mystère d'aliénation lui-même, l'espace intérieur de son agir, tout en l'assumant comme sa blessure de mort et comme la raison voilée de ses rhétoriques d'éclatement et d'agonie sans fin, d'insoutenable dégoût face comme dans le Canto LXXII, au grand usurier Satan-Géryon, prototype des patrons de Churchill.

Que j'entonne le chant de la guerre éternelle, entre la boue et la lumière,

s'intimera-t-il, doctrinalement, au milieu du Canto LLXXII. Ainsi, ce que l'histoire occidentale du monde n'en finit plus de vouloir dissimuler, va transparaître dans les Cantos d'Ezra Pound avec l'intolérable évidence d'une révélation arrachée de haute lutte à la grande nuit déjà régnante, récupérée subversivement sur les établissements des ténèbres en place, sur les avant-postes ennemis marquant la ligne de front des multiples dialectiques de diversion et de crime mobilisés pour aliéner, pour obscurcir comme de l'intérieur tout entendement éveillé des nôtres.

Mais cette poésie de la fin, de l'éclatement crépusculaire et de l'agonie d'une civilisation - celle-ci symbole actuel, elle-même, de toute la succession nocturne de civilisations engagées sur la spirale descendante de la fin négative d'un cycle - comportera aussi, et cachera en elle - souterrainement, très-souterrainement - comme un mince et frais Sunion de dédoublement visionnaire. Car sa mission est non seulement celle de récapituler et de conclure un cycle lui-même en état de conclusion, mais aussi celle de projeter, par-delà les gouffres et comme par réverbération - réverbération cosmique, en réverbération médiumnique aussi - la part secrète de ce qui ne doit pas périr, en aucun cas périr, l'espérance à peine entrouverte d'un autre recommencement, au-delà de Léthé.

18

Une chose en tout cas m'apparaît encore comme à retenir: personne, et ce surtout dans les temps de la fin, personne ne saurait plus respirer l'air raréfié des hauteurs vraiment ultimes, ni donner asile en soi à ce que Hölderlin appelait, dans Brot und Wein, « la plénitude divine », la Göttliche Fülle, sans que celle-ci ne vienne à y laisser ses aveuglante brûlures solaires, ses lissons ardents et son souvenir sans merci, inextinguible et silencieux, extatique.

Si déjà, « au bord de l'abîme », Hölderlin faisait, en écrivant à un ami, sa terrible confession d'état, « maintenant je peux bien le dire, moi aussi Apollon m'a frappé » dans son Canto LXXIV, Ezra Pound ne se définissant-il pas lui-même comme « l'homme sur qui le soleil est descendu » ?

Mais, pareil à Sémélé, rendue incandescente et amoureusement consommée par le feu du ciel, Ezra Pound, frappé lui aussi, par le soleil, transforme ce feu en lumière et devient lui-même lumière, chant ininterrompu célébrant les noces à la fois sauvages et extatiques du ciel et de la terre et la naissance théurgique du troisième terme, du troisième état apollinien de l'être. La poésie, comme Artémise, n'appartient-elle pas entièrement à Apollon ? Et comme Orphée, Apollon n'est-il pas, aussi, un Dieu Noir ?

Ainsi, marquée par « la lumière noire d'Apollon » qu'avait entrevue, un jour Aimé Patri, par cette mystérieuse et troublante « lumière des loups » dont parlent les traditions hyperboréenne de la Grèce antérieure, l'existence d'Ezra Pound n'aura été qu'un long et terrible vertige d'écartèlement au-dessus des gouffres intérieurs de l'état d'exil, de l'état de loup-garou dans l'appartenance occulte du Dieu Noir, de l'Apollon lui-même crucifié sur les ténèbres intérieurs du soleil, au-dessus du Puits du Soleil ?

19

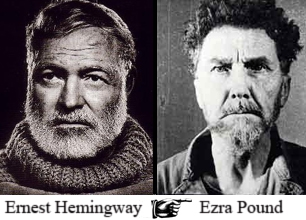

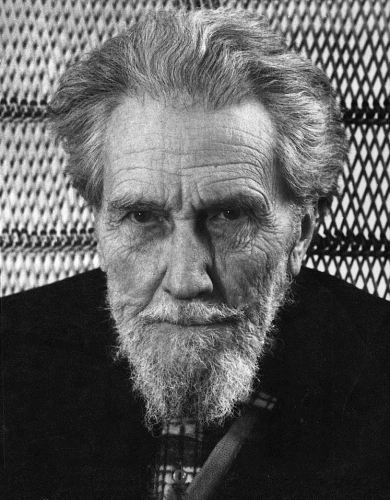

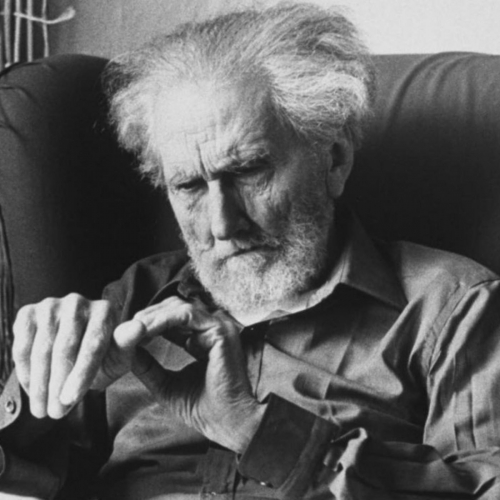

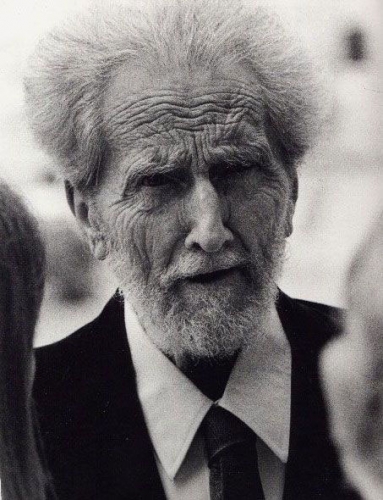

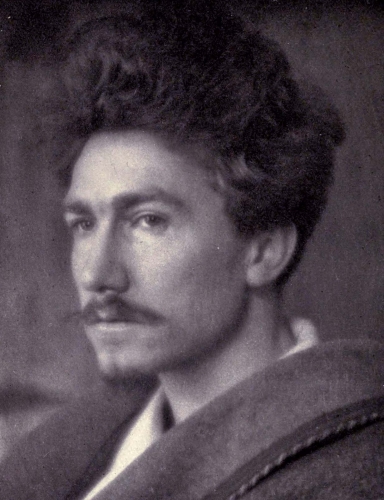

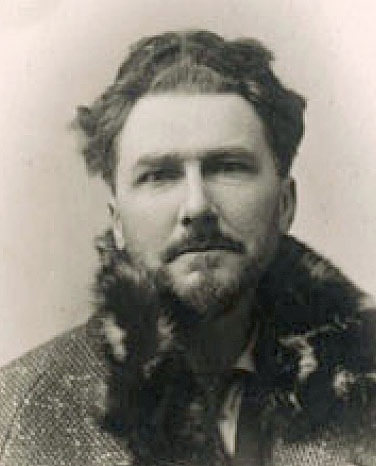

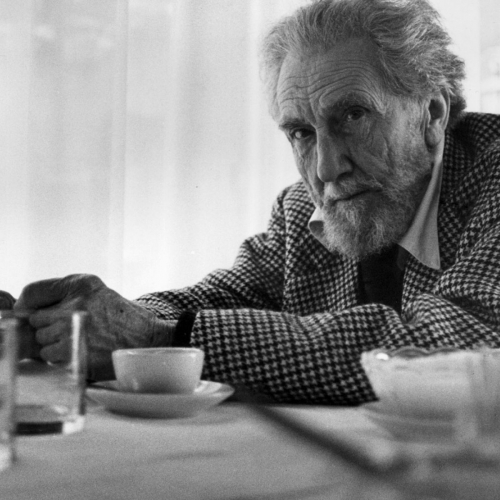

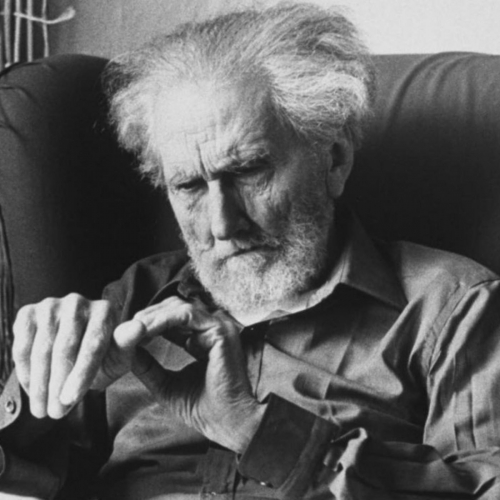

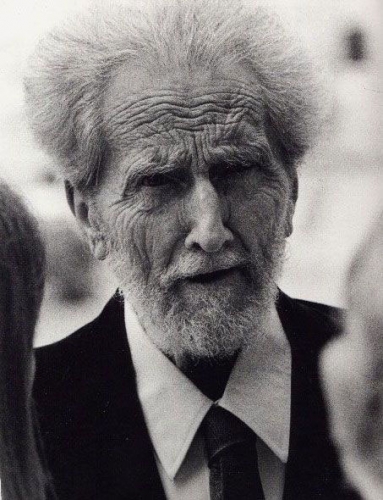

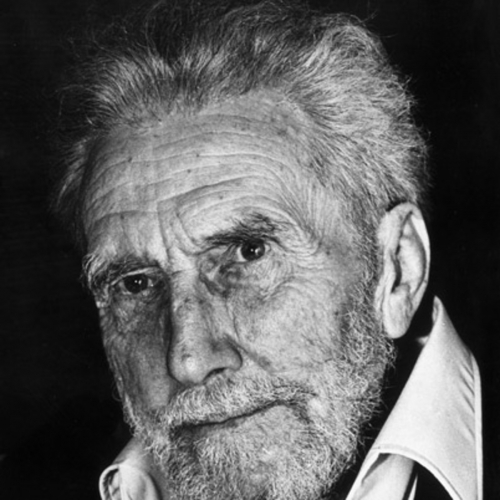

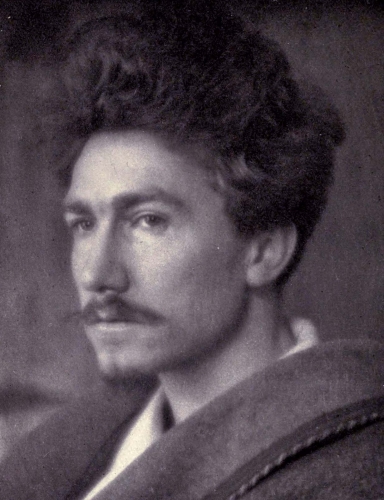

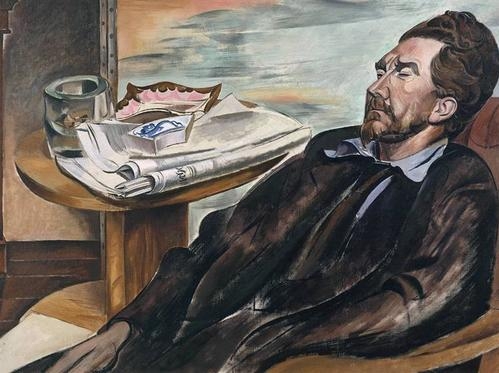

Né en 1885, dans l'Idaho, terre de l'Ouest profond traversée, sur ses hauts plateaux désertiques, par la rivière Snake, l'ancienne Rivière des Sorciers, Ezra Pound s'exilait des Etats-Unis en 19O7, où il ne devait retourner qu’en 1945, quarante ans plus tard, pour être jugé sous le chef d'accusation de « haute trahison en temps de guerre », haute trahison perpétrée en faveur des puissance de l'Axe et principalement en faveur de l'Italie, et pour se voir, éventuellement, condamné à mort. Cependant, reconnu comme « dément », dans « l'impossibilité d'être jugé » et nécessitant d'être « interné et soigné », jusqu'à nouvel ordre dans un « établissement spécialisé », dans un « asile d'aliénés fédéral », Ezra Pound échappa de justesse - miraculeusement même - à la corde, pour être interné à l'hôpital Saint-Elisabeth, à Washington.

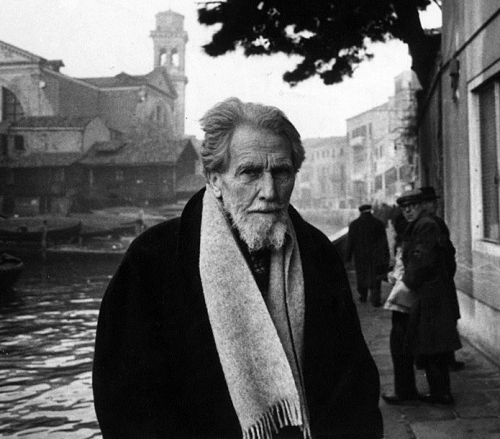

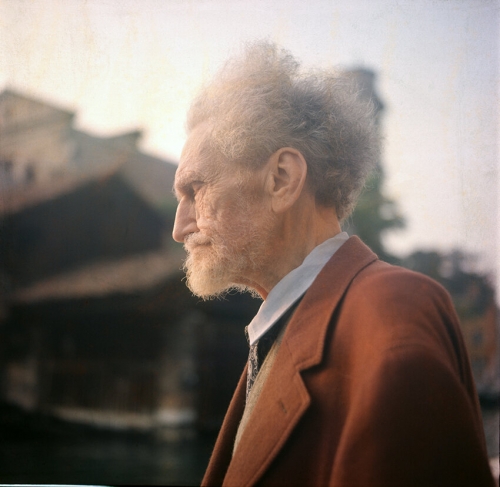

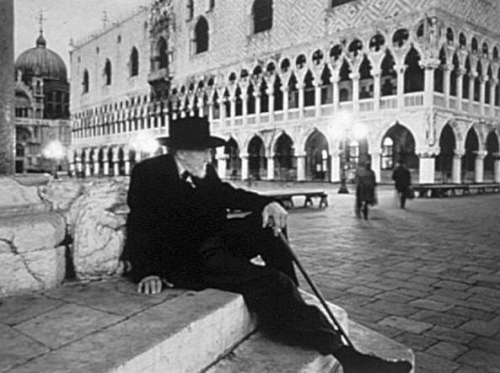

Ainsi, après treize ans de « détention psychiatrique » - ce qui précède et pulvérise tous les records soviétiques en la matière - l'immense visionnaire occidental et roman des Cantos Pisanos quittait les Etats-Unis en 1959 pour ne plus jamais y retourner, puisqu’il est mort à Venise et 1972 - le jour du 1er novembre - et enterré dans une petite île au large de Venise, en terre adriatique.

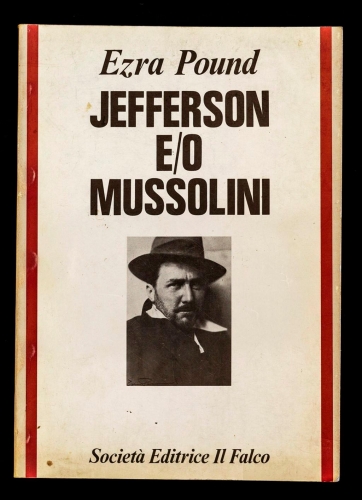

Pendant la dernière guerre mondiale, en effet, Ezra Pound avait assuré une série d'émissions américaines à Radio-Rome, dans laquelle il exhortait la nation américaine à se ressaisir, à prendre conscience de la signification cachée, interdite et prohibitionniste, dévoyée à dessein, d'une guerre allant fondamentalement contre le destin profond et les intérêts les plus vitaux des Etats-Unis dans le monde, d'une guerre d'aliénation nationale et servant des buts étrangers si ce n'est subversivement antagonistes à la vocation, au souffle et à l'être supérieur de ses peuples.

Dans un témoignage intitulé Tombeau pour Ezra Pound, Dominique Jamet écrivait, le 3 juin 1986, dans les colonnes du Quotidien de Paris:

« La décision de l'incarcérer postulait qu'une autorité supérieure à la sienne le rangeait, en toute connaissance de cause, au nombre des individus dangereux, pour lui-même et pour les autres. Pour avoir été fasciste, il fallait que Pound eût été fou. C'était faire bon marché de la santé mentale de quelques centaines de millions d'êtres humains qu'avait séduits l'idéologie dominante du deuxième tiers du siècle. »

« Fallait-il être fou pour se proclamer indifférent à la guerre suicidaire, absurde, qu'engageait une moitié de l'humanité contre l'autre ? Fallait-il être foi pour crier que dans cette guerre allaient s'engloutir les vestiges de la civilisation ? Il fallait sans doute l'être, ou aveugle, ne fût-ce qu'à ses intérêts, pour parler à la radio italienne alors que les Américains étaient entrés en guerre contre l'Italie fasciste. Il fallait être fou ou aveugle, pour ne pas renier les idéaux défaits alors même que la défaite emportait le Reich millénaire et le nouvel Empire romain. Mais était-ce folie que de dénoncer la nouvelle barbarie qui déferlait sur le monde ? »

20

Arrêté en Italie par les forces américaines d'invasion à la fin du printemps fatal de 1944, ou plutôt « livré par les partisans », Ezra Pound, avant qu'on ne l'expédie par avion à Washington, devait passer six semaines - les quarante jours et les quarante nuits des grandes épreuves initiatiques, des grandes descentes infernales, - dans l'enceinte du DTC américain de Pise.

Exposé au milieu du camp, ses compatriotes - ses soi-disant compatriotes - l'avaient enfermé, seul, dans une « cage à gorille » en poutrelles métalliques, entièrement à l'air libre et sans toit, en plein hiver et la nuit un projecteur aveuglant - à dessein - braqué en permanence sur lui. Ce fut ainsi.

Exposé au milieu du camp, ses compatriotes - ses soi-disant compatriotes - l'avaient enfermé, seul, dans une « cage à gorille » en poutrelles métalliques, entièrement à l'air libre et sans toit, en plein hiver et la nuit un projecteur aveuglant - à dessein - braqué en permanence sur lui. Ce fut ainsi.

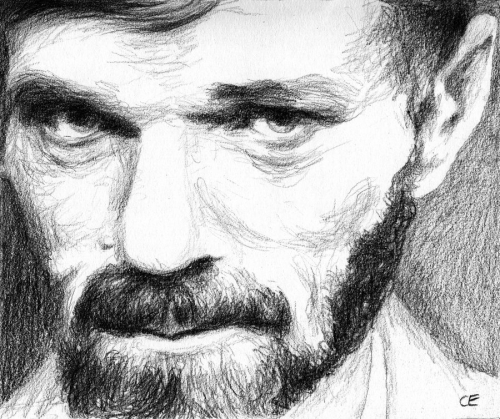

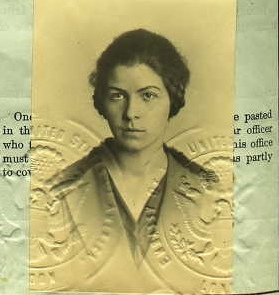

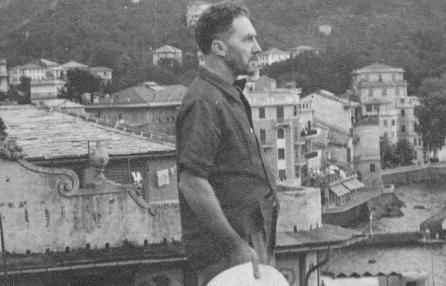

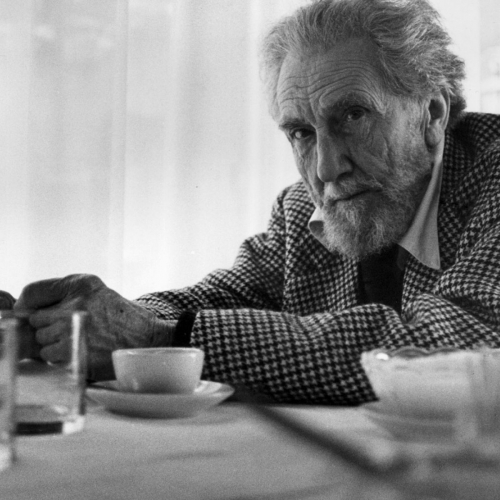

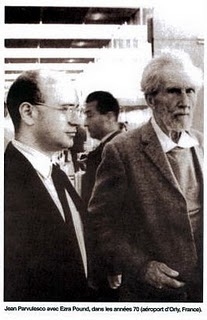

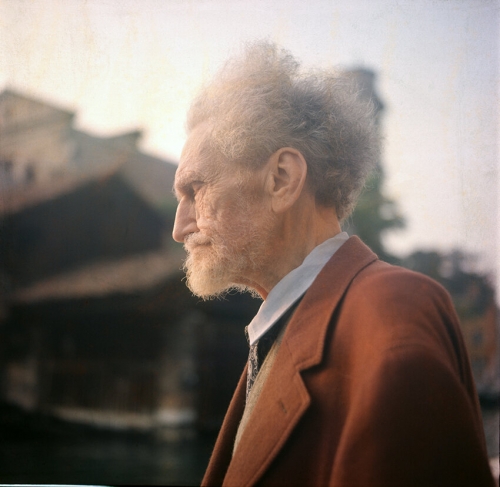

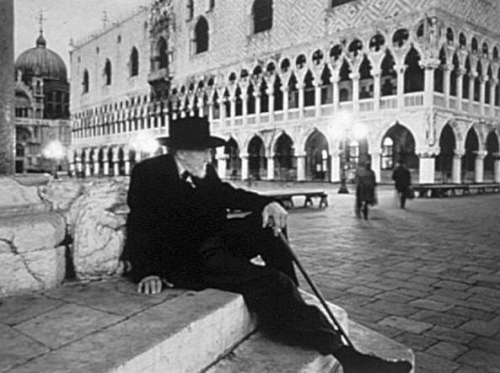

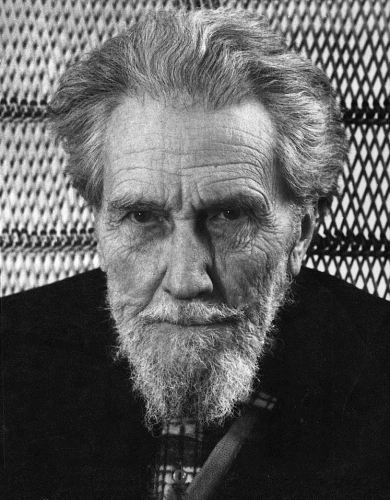

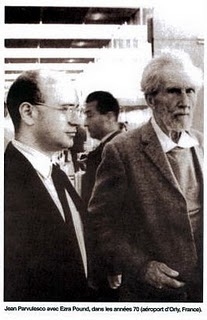

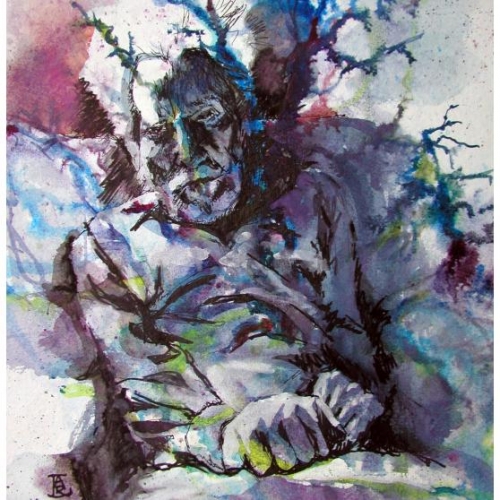

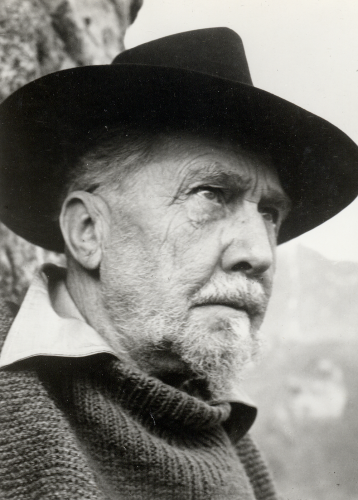

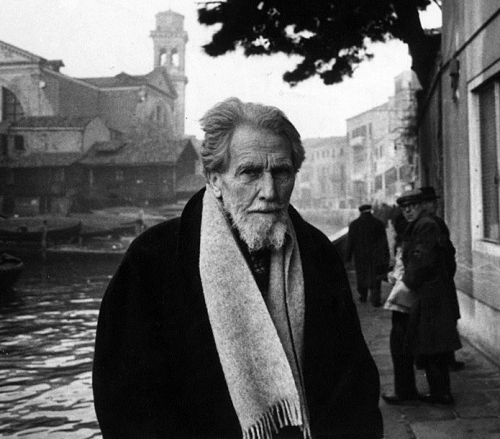

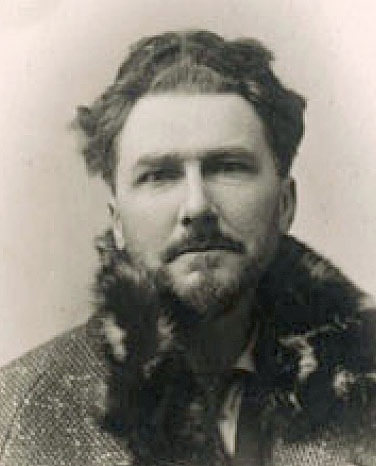

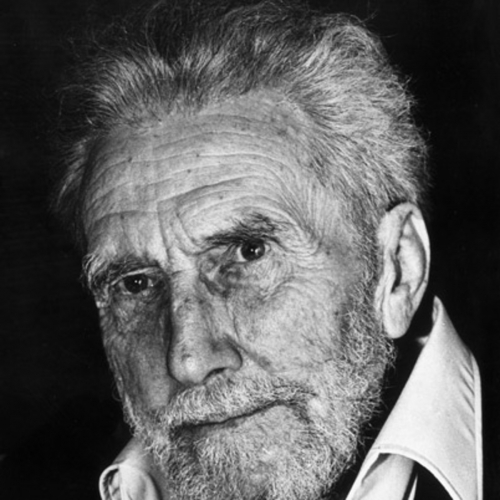

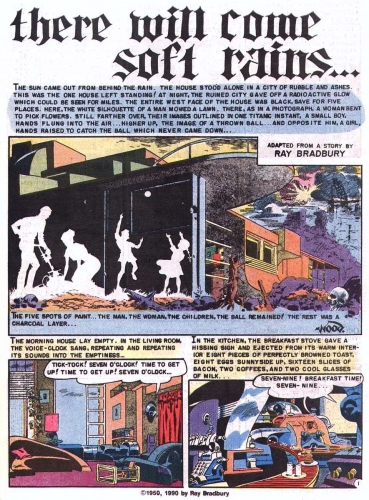

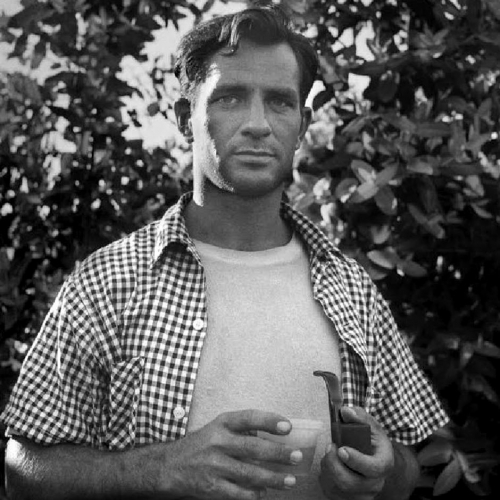

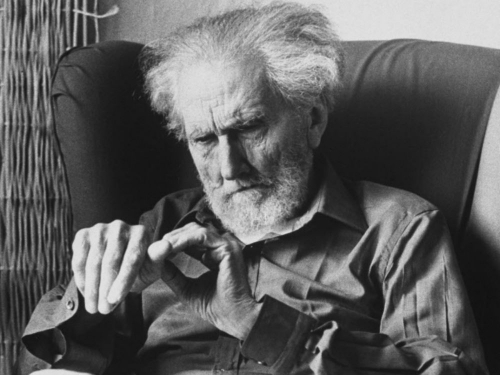

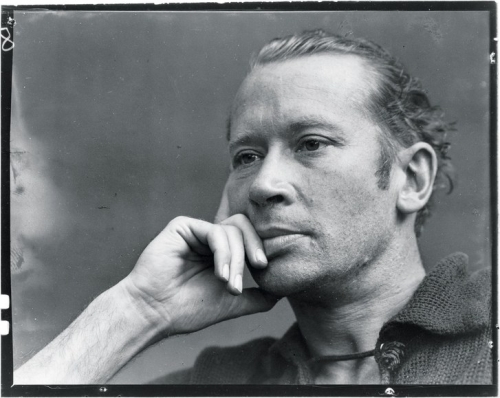

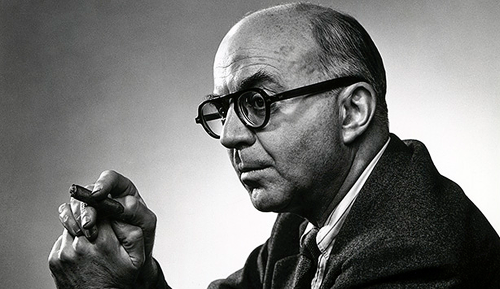

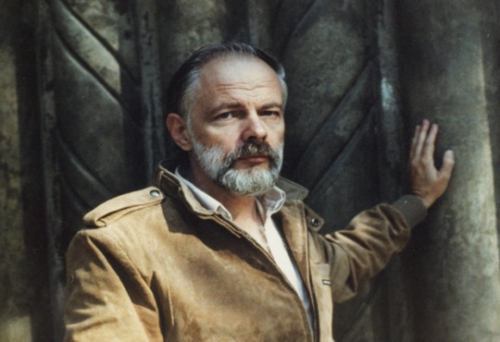

Photo: Jean Parvulesco et Ezra Pound à Paris

Ezra Pound, instance supremissime du cycle fondationnel d'une civilisation occidentale finale, démiurge de la saison poétique - de la grande saison ontologique - appelée à conclure et à recommencer apocalyptiquement ce qui, avant lui, eut à instruire, et depuis quels abîmes, le chant originel de Virgile, de Dante, de Hölderlin, Ezra Pound, « l'homme sur qui le soleil est descendu », avait à ce moment-là soixante ans, et les deux derniers vers des Cantos Pisanos, écrits dans sa « cage à gorille », ne sont qu'un insondable cri de désespoir, de honte terrifiante et nue:

« Si le gel te mord sous la bâche

Tu crieras "pitié" à la fin de la nuit. »

21

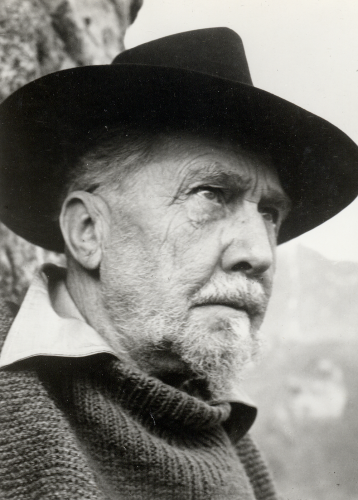

Ayant eu moi-même le privilège, que j'estime des plus extraordinaires, d'approcher personnellement, et de la façon la plus conséquente, l'auteur des Cantos Pisanos lors de ses derniers passages à Paris, je peux témoigne directement de son appartenance à un autre niveau d'être - un autre niveau de l'être - tout autant que de la réalité magnétique, du rayonnement intolérablement paroxystique de sa présence immédiate, de son influence charismatique directe, qui n'en finissaient plus d'agir sous le vœu orphique du silence total , de la renonciation acharnée à la parole, à toute parole, vœu et barrière par lesquels il manifestait sa volonté d'absence d'un monde irrémédiablement en proie, depuis « le printemps fatal de 1945 », aux puissances du chaos et du néant. (...)

Que ta clémence, Perséphone, se maintienne,

priait, au début du siècle, le jeune Ezra Pound, dans un sonnet aux cadences, aux implications extraordinaires proches de celles des plus occultes confréries de Fidèles d'Amour.

Et ces implications détenant, je ne suis pas très-loin de le penser, la clef décisive de toute intelligence amoureuse de l'œuvre d'Ezra Pound, je veux dire de toute intelligence concernant les pouvoir cachés et la lumière cachée se dégageant d'une certaine expérience amoureuse, aussi spéciale qu'elle dût avoir été totale, et dont le parcours, dont l'action souterraine semblant avoir secrètement contrôlé, et de quelle dramatique manière, la vie et l'œuvre d'Ezra Pound. Et quand je parle de pouvoirs cachés, comment ne pas se demander, aussi, quelles peuvent bien avoir été les origines cachées de ces pouvoirs ?

Vertige solaire final, à partir des vertiges solaires des commencements. Quel aura donc été le plus profond secret de vie d'Ezra Pound ? Dans son œuvre, il faut se résigner à la reconnaître, il n'y en a pas la moindre trace: pour y être quelque peu admis à en connaître, il faut avoir eu accès à la part confidentielle de son existence, et celle-ci, je peux l'affirmer avec force, se trouve à jamais hors d'atteinte, sauvegardée d'avance de toute ingérence extérieure à ce qu'avait été son excellence propre, sa « plus haulte vertu ».

Et ce que moi j'avais été reçu à savoir, initiatiquement parlant, sur la « carrière amoureuse » d'Ezra Pound, personne d'autre que moi ne le sait aujourd'hui.

L'amour absolu conduit au pouvoir absolu, dont la poésie absolue n'est que l'aura irradiante, la lumière à l'extérieur, le resplendissement boréal.

22

Le soir du Décameron, quand Olga Rudge me disait: « Je crois que le vieil oncle Ezra est dans les vignes du Seigneur ».

Dans la vie du vieil oncle Ezra, deux femmes, Dorothy Shakespear, et Olga Rudge. Quand Mircea Eliade me confiait que, suivant un ancien secret gnostique redécouvert par lui, la seule voie de divinisation - la seule expérience divinisatrice - restant ouverte aujourd’hui, pour l'humain, est celle d'aimer deux femmes.

On a compris qu'il s'agit en fait d'une voie tantrique. La plus grande sainteté « pouvoir aimer deux femmes à la fois ». C'est l'échec de parcours de cette expérience qui va mener le héros d'un des romans roumains de Mircea Eliade, Paul Anicet, à la résolution du suicide, du « suicide mystique ». Ce roman, non encore traduit en français, s'intitule Le Retour du Paradis. Sans aucun doute le plus important des romans de Mircea Eliade.

Quelle vertigineuse fulguration gnostique Ezra Pound est-il parvenu à établir entre Dorothy Shakespear et Olga Rudge, et quelle fut l'incarnation du troisième terme s'établissant gnostiquement entre elles ? Tre donne intorno alla mia mente, est-il dit dans le Canto LXXXVIII. Confession ? Et quelle fut la Troisième, l'inconnue des gouffres du Feu Sulamitique, le « quatrième feu », et elle-même faisant l'objet, dans la vie de son corps et dans le corps de sa vie, des feux de la très-occulte « clémence de Perséphone » ? Quant aux mystères agissants du « quatrième feu », voir aussi le long chapitre que je consacre à ce sujet dans La Spirale Prophétique.

D'autre part, je relève les « accointances galactiques » dont il faut sans doute créditer Olga Rudge. Des « accointances galactiques » dans le sens même où l'eût entendu H.P. Lovecraft. Dans un sens, je veux dire, immédiatement conspirationnel et métacosmique.

Ainsi que les fort énigmatiques relations tibétaines de Dorothy Shakesear. D'ailleurs, les dix dernières années de la vie d'Ezra Pound furent entièrement situées sous une certaine lumière tibétaine. A travers le mariage de sa fille, des liens d'étroit rapprochement s'établissent, pour Ezra Pound, avec le Tibet, et avec certaine mouvance tibétaine en Europe, parmi les plus discrètes.

Ezra Pound, « figure solaire » de Dionysos. S'identifiant au grand chat sauvage des Montagne Rocheuses de son enfance, Ezra Pound en reproduit les feulements enragés quand il donnera personnellement lecture de ses Cantos. On y reconnaît l'identification dionysiaque par excellence, celle de « l'homme léopard ».

Sur ce que, refermées sur elles-mêmes, les anciennes confréries dionysiaques appelaient le « pacte du silence ». Ezra Pound, on l'a dit ici-même, s'était complètement tu pendant une dizaine d'année, jusqu'à devenir « dépourvu de parole ». Il n'avait accepté de « reprendre parole » que la nuit du diner chez Dominique de Roux, rue boulevard Saint-Germain, quand il avait cru qu'il lui fallait me dire, coûte que coûte, ce qu'il pensait du livre que je venais de lui consacrer, livre qui, depuis, s'est perdu. Et la suite hallucinée de ses confidences, axées, pour la plupart, sur la Sicile.

(...)

24

Et pourtant, malgré la distance peut-être infranchissable entre les autres, quels qu'ils fussent, et son exil à l'intérieur même de l'exil, il était impossible d'approcher Ezra Pound sans se rendre compte de ce que je devrais appeler sa bonté, une bonté qui, chez lui, se manifestait pas une disponibilité enthousiaste et sans cesse renouvelée pour le génie des autres, pour tout ce qui lui paraissait pouvoir participer d'une intelligence authentiquement révolutionnaire de la conscience occidentale du monde au moment où celle-ci était appelée à faire face en catastrophe à la première lame de fond de la montée finale des forces négative du chaos et du néant. « Tout aux autres ». Elingue prédestiné, qui n'a-t-il pas soulevé de terre ?

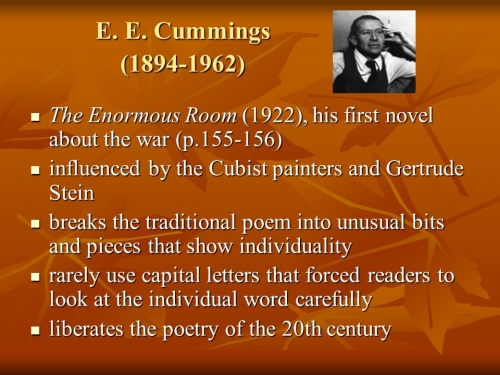

Joyce, Brancusi, Cummings, Eliot, les plus grands noms de la littérature et de l'art occidental modernes restent profondément redevables, dans leurs manifestations ultérieures, de l'attention active, de la volonté enthousiaste et stratégiquement efficace, volonté d'intelligence et de soutien immédiat, avec lesquelles Ezra Pound s'était tourné, au moment le plus critique, vers le devenir, vers la situation de leur œuvre en marche. C'est sur l'intervention personnelle d'Ezra Pound que Harriet Weaver s'était décidée à « donner à Joyce », écrit G.S Fraser, « tout l'argent qu'il lui fallait pour qu'il puisse terminer Ulysses sans être gêné dans sa vie ». Et ce n'est là qu'un seul exemple entre bien d'autres, innombrables. Non point une poussée exceptionnelle, mais la conduite permanente de toute une vie. Une vocation illuminée, une forme de destin et de grandeur. La cristallisation en lui d'une vibration éternelle.

25

Apollon est un Dieu Noir, Apollon est aussi le Destructeur, le Dévastateur: son nom vient d'apollunai, défaire, détruire.

« Nul ne saurait aller au Père si ce n'est par moi ». Nul ne saurait être admis à la vision solaire totale, impériale, à la fois ardente et limpide, d'Apollon Phoibos, le « resplendissement », s'il n'est pas descendu, avant, lui-même, jusqu'à ces tréfonds interdits et obscurs où veille l'Apollon Noir, instructeur et maître de la lumière hyperboréenne du « soleil des loups ». Regarder en face le soleil du jour, c'est avoir su - et surtout pu - neutraliser en soi-même tous les pouvoirs, et jusqu'à la réalité même du soleil noir de la nuit et de la mort, c'est avoir tué la mort par la mort, anéanti la négation fondamentale par une négation trans-fondamentale, une négation d'au-delà de toute négation: c'est réduire l'Urgrund nocturne des origines ontologiques par l'Abgrund préontologique et intransitif, qui n'est ni d'avant ni d'après le lieu originel, mais du non-lieu sans origine aucune d'où tout vient et où tout va. Sans origine ni devenir, exil de l'exil dans l'exil, seule la poésie, le « sentier aryen oublié », livrera l'ouverture occulte vers les chemins qui portent à la délivrance absolue, au salut absolu et aux pouvoirs absolus de l'existence en tant que « concept absolu ».

Ce sentier aryen oublié, qui est peut-être aussi le sentier védique de la poésie la plus grande, est essentiellement un sentier d'exil, de rupture totale, de départ sans retour.

La voie secrète de la poésie la plus grande sera toujours la voie des éternels adieux.

26

Ainsi, « Frères Illuminés de l'Asie », « Fraternité Secrète d'Héliopolis », que sais-je encore, tous les noms sont bons pour monter ce qui ne doit absolument pas être montré: Ezra Pound voyait dans tous ceux qui, comme lui, concouraient à la mise-en-place d'un appareil clandestin de sauvegarde poétique et métahistorique d'une civilisation menacée, happée par la décadence et condamnée à l'anéantissement, les combattants héroïque d'une même cause ontologique, les héros sacrifiés d'avance d'une cause qui n'eût en aucun cas pu prétendre à l'emporter sans être passée par l'épreuve royale de l'or dans la fournaise, sans connaître la ruine finale de son propre temps historique et parcourir liturgiquement l'espace nocturne du mystère de sa défaite la plus irrémédiablement consumée.

Ainsi toute décadence dépassée devient-elle une conspiration active, dont les buts secret n'en finiront plus de se retourner contre elle-même.

27

- Dépassement, aussi, des tout derniers états de la conscience nationale par la conscience naissante, par le pressentiment hypnotique de la catastrophe générale.

- Déchéance américaine, déchéance occidentale, européenne, planétaire. L'obscurcissement intérieur d'un cycle à sa fin, le vertige en marche de la spirale intérieure d'une civilisation crépusculaire, de plus en plus nocturne.

- Déchéance d'une nation, d'une race, d'un sang, d'une souche métacosmique dévaluée, en voie d'auto-anéantissement - (H.P Lovecraft, « Insmouth »).

- Conclusion apocalyptique d’un cycle, inventaire de ce qui ne doit pas périr, de ce qui passera par-dessus les tumultes, les cauchemars de ka ligne du partage apocalyptique des « eaux de la fin » qui seront, surtout, des « eaux de feu ».

- Le ministère final de cet inventaire apocalyptique revenant, pour Ezra Pound, comme une prédestination de droit, aux tenants de la poésie en action, aux sacrifiés extatiques de la grande poésie.

- Au commencement et à la fin: c'est la poésie qui commence, c'est la poésie qui juge et qui anéantit, c'est la poésie qui juge et qui sauve.

- Clandestinité historique du Logos en action, la poésie est essentiellement guerre occulte, subversion et pétition permanente d'un renversement métahistorique total dont l'achèvement - quand viendra-t-il, quand, quand, quand - l'accomplit tout en la détruisant et la détruit tout en l'accomplissant, glorieuse et sereine.

28

Or, toute sa vie d'homme Ezra Pound l'a vécue hors de la terre humble et sauvage qui l'a vu naître et ses treize dernières années de séjour dans les établissement gouvernementaux de détention et de contrôle psychiatrique de Washington représentent sans doute la forme la plus tragiquement noire et destituante de l'être engagé dans l'escalade de l'exil intérieur, qui est à la fois l'exil dans l'exil et l'exil à l'intérieur, dans le sens où, jadis, on parlait d' « émigrés de l'intérieur »: le renversement dialectique finale qui fait, comme dans le cas d'Ezra Pound ramené de force aux Etats-Unis, le dernier état de l'exil de la terre même du retour, n'est pas le dédoublement de l'exil, mais l'annulation définitive de tout espoir de retour dans la mesure même où la liberté, la salut et l'honneur ne sont plus donnés, et encore moins rendus par les retrouvailles de l'exilé avec sa terre originelle. Et d'autre part, quelle est la terre originelle de notre actuel exil ontologique à nous tous ?

Ainsi se fait-il qu'en cette extrémité dernière de notre expérience crépusculaire de l'histoire et du monde, le salut, la liberté et l'honneur ne sont plus à chercher que dans le départ à nouveau, que dans le deuxième départ et dans le départ sans fin de celui pour qui désormais l'origine se confond avec la fin, le désastre avec la gloire et l'oubli le plus total de soi-même et du monde avec la mémoire totale d'au-delà toute mémoire. Mais il s'agit d'une mémoire immémoriale, antérieure à tout oubli, à tout désastre et toute fin obscure, et dont l'antériorité ne se pose plus dans le temps, mais hors du temps, ontologiquement: chaque fois que quelqu'un se souvient de ce qui se situe indéfiniment au-delà de l'oubli, le monde de l'oubli disparaît comme par enchantement, et c'est bien là, dans la soudaine rupture des interdits, que réside et se lève le souffle vivant de la part à jamais hors d'atteinte du double mystère hyperboréen - mystère de la glace et mystère du feu - agissant à travers la spirale ascendante de l' « éternel retour » du Sang Majeur.

Et qu'est-ce que la grande poésie, ce que nous appelons la grand poésie, si ce n'est le chant du Sang Majeur ?

29

Car c'est bien par le départ que l'exil se déclare et, tout comme l'os qui blanchit au fond de la blessure ouverte, c'est dans le départ que le destin se laisse, ou plutôt se donne à dévoiler: mais, si le destin le plus monolithique n'est jamais que le retour à l'être et, de par ce retour même, fondation nouvelle et nouveau commencement, et si c'est dans la rupture des digues et dans la dévastation des anciennes fondations, dans le déracinement et dans le désespoir que tout renouveau prend ainsi naissance, combien plus profond encore ne sera-t-il donc alors le destin enraciné dans le déracinement même, l'exil dont l'espérance n'est plus tournée vers le retour mais vers l'horizon agonique, vers la remise en question infinie d'un exil plus éloignant que tout exil, l'exil de l'exil dans l'exil ? Or c'est bien ainsi que se pose le problème de l'exil d'Ezra Pound, dont la poésie est aussi ce par quoi tout nous est désormais devenu exil, et exil à jamais.

30

La poésie fondationnelle des cycles métahistoriques, celle de Virgile, de Dante, de Hölderlin ou d'Ezra Pound, n'interpelle jamais la réalité immédiate, ne traite jamais directement de la réalité immédiate du monde qui est supposé être le leur, mais uniquement - toujours et jamais autrement - des figurations mythologiques particulières de cette réalité, qu'elles fussent religieuses, existentielles et tragique ou, lors des grandes saisons de désertification spirituelle, des figurations rhétoriques se suffisant à elles-mêmes, des « figurations de figuration », des figurations « culturelles », plutôt honteuses, « post-créationnelles », savantes.

Encore une fois: pour trouver et se donner le matériau de travail nécessaire à son affirmation, cette poésie des sommets et de l'agonie n'interpellera chaque fois que seule la culture de son époque, la culture seule dont elle est tenue d'établir la conclusion, la figure assomptionnelle suprême, et non la réalité directe du monde dont cette culture veut s'imposer comme la conscience vivante, comme l'interpellation chiffrée par les signes de ses rhétoriques en action, et finalement, et toujours, comme le masque d'or théologique. A la fin seules les théologies l'emportent.

Le cas de Hölderlin serait-il différent, dont les échappées lyriques l'emportent souvent - mais là aussi n'est-ce pas apparence, seule apparence - sur la sommation prophétiques de ses grands hymnes supra-historiques, de son hymnein ontologique ? La preuve qu'il n'en n'est rien, on la trouvera dans la tragédie de l'autodissolution de son moi dans l'ensemble de la vision sémiologique de la vision qui fut la sienne, qui lui appartint avant qu'il ne finisse lui-même par lui appartenir: c'est quand il parlait apparemment le plus de lui-même, au paroxysme ultime de l'incandescence lyrique du « chant enclos », que Hölderlin ouvrait les vannes de la remontée dévastatrice de l'être, de l'être - on me comprend - conçu dans les dissimulation tragiques et nocturnes - nocturnissimes - que l'on sait préposées aux temps de l'impuissance, de la sècheresse et de l'oubli. Les temps, autant le dire, de notre propre impuissance, de notre propre dessèchement, de notre propre oubli. C'est quand s'effaçait de plus en plus irrévocablement devant le ministère mythologique et fondationnel de son chant prédestiné, le chant d'un monde dont il devait ainsi devenir, en cessant totalement d'être lui-même, le vertige occulte de l'impersonnalisation absolue et le « concept absolu », que Hölderlin accédait à son identité ultime, supra-personnelle et supra-historique, à son identité dogmatique, mythologique et « divine ».

Longtemps, très-longtemps, à Tübingen, sur les rives du Neckart, Hölderlin sut montrer qu'il n'était plus lui-même, qu'il était devenu - définitivement - cette Allemagne éternelle dont la figure préontologique était censée illuminer, depuis les hauteurs, la totalité du cycle de destin continental qu'il avait ramené, lui-même, à ses principes, à son être eidétique, où la Garonne s'identifiait visionnairement - hypnagogiquement - avec le Rhin, avec l'Oxus, avec l'Indus, avec la rivière éternelle de l'être se rejoignant lui-même à travers le lointain des terres, des sables, des gouffres occultes du non-être et de ses dominations d'ombre.

Mais, d'autre part, le long sommeil dogmatique de son engouffrement dans le mystère orphique de la dépersonnalisation, Hölderlin ne l'a-t-il vécu, aussi, comme l'élévation extatique et pacifiée, infiniment pacifiante de ce qui, en lui, et par lui, avait ainsi établi, encore une fois, et combien secrètement, la gloire de son règne ?

31

Or ce même processus de dépersonnalisation existentielle apparaîtra aussi en des temps encore plus obscurs, et hypnagogiquement, avec le chuchotement mythologique de la romance de James Joyce, le Finnegan's Wake.

Ici, qui chante ? Et les abîmes lumineux du sommeil dogmatique de la dépersonnalisation, de la dépersonnalisation qui définit et dénonce, qui démantèle sans fin la « personnalité » supposée de l'écrivain James Joyce ainsi vertigineusement dissoute dans son propre chant avançant à travers le songe et avec tourbillons écumants de la rivière Anna-Livia Plurabelle, ces abîmes du sommeil de l'auto-dépersonnalisation mythologique de quelqu'un, mais de qui - de qui désormais - ces abîmes de la plus abyssale mémoire celtique de la plus grande immémoire du cycle, ne sont-ils finalement pas les mêmes - quelque part - dans l'œuvre poétique d'Ezra Pound, quand ils y apparaissent ?

32

La conscience totale et totalisante, polaire, la conscience littéralement totalitaire qui est celle des Cantos d'Ezra Pound par rapport aux vastes ensembles de ratissage « culturel » constituant - et sans cesse reconstituant - leur charge d'ouverture domaniale, vouée, celle-ci, exclusivement, à fournir l'exaltation réverbérante, le pathos déchirant du chant unique œuvrant comme pour son propre compte alors qu'il n'y œuvre que pour le compte de cela même dont le destin est de tout lui prendre, cette conscience ainsi réputée totalitaire n'est-elle pas, de par cela même, une conscience intemporelle, fondamentalement dépersonnalisée, où tout se doit, où tout est ramené - se doit d'être ramené - au seul présent dévotionnel de cette parousie ininterrompue dont les Cantos se nourrissent et vivent, parousie de leurs propres entrailles solaires, saisissables uniquement dans, et, surtout, par l'ensemble des chants en action, et jamais aux stations, aux étapes intérieures de cet ensemble, jamais au niveau d'un seul Canto ? Et là le mot à retenir est celui de parousie.

Car, à l'instant même où, dans l'aventure d'une lecture - d'une récitation - intérieurement liturgique des Cantos d'Ezra Pound, on cesse de regarder en face le terrifiant soleil blanc de leur unité ontologique, le chant s'en trouve suspendu, et cesse, devient lettre suspecte d'un ensemble expirant, comateux, et comme lettre morte, à peine non-signifiante, cadavre dépecé et vertige obscurantiste, « culturel », de mots en interruption d'œuvre vive, voire, comme disaient les autres, « cadavre exquis ».

33

Dans un certain sens, les rapports situant l'émergence de la non-identité personnelle du porteur du chant dans les Cantos d'Ezra Pound - ou dans le Finnegan's Wake, ou dans les hymnes hölderlinien de la série prophétique et mythologique finale - face à l'ensemble de l'œuvre en action et souverainement régie, dans sa marche, par cette même émergence précisément, sont les mêmes rapports que ceux dont on entend qu’ils établissent , dans la phénoménologie husserlienne, l'élévation d'un Je transcendantal au centre et au-dessous - élévation à vrai dire combien mystérieuse quand elle parvient à se faire agissante - de la conscience qui, de conscience en conscience passe illégalement, gnostiquement, à l'état de conscience des consciences.

Qui l'eût cru ? Des noces clandestines de Meister Eckhart et de la Kabbale Juive, une lumière gnostique émane, qui sert, aussi, à illuminer en profondeur le secret institutionnel des Cantos Pisanos.

La répugnance que j'ai toujours ressentie à l'égard de la phénoménologie husserlienne en vase clos ne m'empêchera quand même pas d'y reconnaître les fers de l'ancienne griffe gnostique alexandrine, les feux spirituels qu'une gloire judaïque aussi clandestine qu'illégale religieusement, mais illuminée, opératoire, surpuissante et sainte très-certainement, que l'autre judaïsme n'a jamais voulu reconnaître et moins encore s'en concéder les fruits ardents, d'outre-monde, salvateurs et de maniement extrêmement périlleux. Encore que là-dessus, bien des choses resteraient à redire. Et des plus excitantes. Canto LXXVI, évoquant ces briques que l'on croit nées ex nihil.

34

Dans ses Cantos Pisanos - j'ai décidé d'appeler, désormais, tous ses Cantos du nom coronaire final de Cantos Pisanos, en souvenir très précisément, de ce qui lui fut fait à Pise - dans ses Cantos Pisanos, dis-je, Ezra Pound procèdera toujours par la dialectique opératoire - essentiellement gnostique, et je dirais même alexandrine - des accumulations, mais la mission de ses accumulations n'est pas celle d'épuiser exhaustivement le domaine de la matière culturelle occidentale de la fin ( disons, aussi, que j'utilise ici le terme de manière occidentale comme certains celtisant arthurien parlaient de la « matière de Bretagne »).

La mission propre des accumulations culturelles occidentale dans ses Cantos Pisanos, Ezra Pound la conçoit sur un mode en quelque sorte héraldique, destiné à établir comme une micronésie aussi éclatée qu'ardente, comme une grille sémiologique s'ensemble, engagée à mobiliser et à annoncer, à dénominer - et cette dénomination sera très hautement opératoire, gnostique et métacosmique dans ses œuvres ultimes - une accumulation sérielle d'accumulation dont les habilitation intimes se proposeront en effet de feindre de disposer - je veux dire de disposer symboliquement, voire magiquement - de la totalité culturelle de la « matière d'Occident » émergeant en cette fin occidentale du cycle de la fin, du grand Cycle de la Fin.

Les accumulations opératoires de la poésie des Cantos Pisanos ne prétendent en rien absolument à procéder à des amoncellements, à des bancs de données culturelles se donnant je ne sais quelle mission secrète préservatrice, désespérée par le tour que prennent les choses, ses accumulations n'ont d'autre identité que celle du pathos magicien et héraldique destiné à les porter vers ce qu'il faudrait peut-être convenir d'appeler leur réalité idéale, dodécaphonique.

Rien, absolument rien n'existe dans les Cantos Pisanos au niveau de la partie, tout y est accumulation et toute accumulation est engagée à s'auto-anéantir à l'instant même où elle se constitue en vue d'être admise à soutenir l'unique chant, le chant transcendantal qui émane - dans le sens gnostique du terme - de la seule totalité constituante et constituée des Cantos Pisanos dans leur ensemble dit et non-dit, et cette totalité elle-même se rompant, éclatant sans fin, une fois ainsi instituée, pour redescendre ders le gravier non-intentionné de ses parties, là où elles de trouvent et come elles s'y trouvent, de ses parties qui la soutiennent secrètement tout comme le gravier soutient la courant étincelant, limpide, de la rivière qui va, vers où elle va.

35

Il est à relever, d'autre part, que le traitement des parties extrême-orientale des Cantos Pisanos - ou de je ne sais quelles négritudes données pour transcendantales, fiction symbolique où Ezra Pound suit les obsessions atalantes de Léo Frobenius - appartient à une politique d'exploitation exclusivement culturelle de la matière d'occident, où les appellations extra-occidentale, quelles qu'elles fusent, ne sont admises à être utilisées que dans la seule mesure où elles peuvent justifier d'un intérêt que leur eût port" quelqu’un des nôtres et à l'intérieur d'une aire d'habilitation réellement occidentale. Tout compte fait, ce n'est pas tellement l'écriture chinoise qu'intéressera Ezra Pound, mais l'intérêt que Fenollos avait porté à celle-ci, etc.

36

Le dessein occulte à l'œuvre dans les Cantos Pisanos prétend-t-il mobiliser, embrasser poétiquement la totalité de la culture occidentale concernée par la conclusion catastrophique de ce cycle final du Kali-Yuga, à elle seule cette prétention - ne fût-ce qu'en tant que prétention seule, et rien qu'une prétention avouée, proclamée subversivement - va aussitôt substantialiser la mise en symbole du processus ainsi déclenché, entamer la dialectique de son auto-transcendance, de la soudaine émergence en son sein du chant totalisateur, du pôle d'attraction active d'où procède la mystère du chant unique. Ne bougez point, laissez parler le vent: le Paradis est là, Canto CXX.

Comme le feu courant dans la plaine embrasée, et qui flambe haut, l'œcuménicité d'état du symbole de la totalité de l'aire culturelle à laquelle Ezra Pound en appelle ainsi fera que les choses apparaissent d'avance comme si elles étaient ainsi, et c'est cette apparence même - et sa substantialisation, sa mise-en-chant - qui constituait le but caché de l'opération menée, par lui, de main de maître. Une apparence acceptée comme symbole abyssal de ce qu'elle représente devenant, de par cela même, le noyau vivant de ce qui s'y trouve représenté, son "Je transcendantal". « Qui t'a fait roi ? » « La royauté », ou, plutôt, « ma propre royauté ».

37

Ainsi en viendra-t-on à comprendre qu'une lecture doctrinalement et philosophiquement légitimée des Cantos Pisanos équivaut réellement à une expérience gnostique en profondeur, que les pouvoirs supérieurs d'une certaine poésie secrètement comprise - conduisent à l'intelligence existentielle, autrement dit la participation liturgique directe et immédiate aux mystères fondationnels d'une civilisation accédant à la conscience dépersonnalisante de soi-même à l'instant précis où - or tout est dans cet instant - le processus dialectique final est entamé qui, d'une part, doit en prévoir l'auto-anéantissement à brève échéance mais, qui, d'autre part, ne doit pas moins veiller à ce qu'il y ait passage vers l'imprépensable des recommencements, de la reprise du souffle en vue des prochains grands cycles métacosmiques à maîtriser.

Je dois signaler que le concept d'imprépensable je l'emprunte, dans son acception ontologique, à Martin Heidegger.

Enfin, chose également à ne pas passer sous silence, la poésie vivante et agissante des Cantos Pisanos n'est pas seulement à proposer l'institution accélérée de l'Arche Métasymbolique de nos temps voués à l'auto-anéantissement, elle est elle-même, ontologiquement - et de par elle-même, révolutionnairement - cette Arche Métasymbolique.

Enfin, chose également à ne pas passer sous silence, la poésie vivante et agissante des Cantos Pisanos n'est pas seulement à proposer l'institution accélérée de l'Arche Métasymbolique de nos temps voués à l'auto-anéantissement, elle est elle-même, ontologiquement - et de par elle-même, révolutionnairement - cette Arche Métasymbolique.

Ainsi les armes de la poésie des Cantos Pisanos doivent-elles exhiber, comme devise, l'ancien mot diplomatique des nôtres, et in Arcadia ego.

38

Ezra Pound: « L'ingenio est immortel, le temps n'en a pas fait sa proie ». Récapitulations actives:

- au commencement, le ministère de la poésie accuse la transparence, le pathos royal et orphique, le mystère du nommer, le mystère du fonder (" Ce qui demeure, les poètes le fondent").

- à la fin du cycle: reconnaître le sien, redire, rappeler hypnagogiquement, s'utiliser à choisir ce qui doit rester, parvenir à emprunter une voie de passage vers le cycle suivant, par-delà l'abîme final.

Dans la poésie d'Ezra Pound, intercepter intérieurement le chant d'un monde solaire soigneusement dissimulé, va vibration intérieure, son « rayon vert » : le chant mémoire d'une monde solaire devenant, à son crépuscule, la mémoire ce chant, la mémoire qui chant qui s'éteint, du « chant perdu ».

- certitude du retour, certitude gnostique du retour du soleil, du Sol Invictus.

- « vertige solaire final, à partir des éclats du vertige solaire des commencement ».

- or, à présent, la dernière interrogation accédant, à bout de souffle, à la formulation apocalyptique par excellence, quel sera son nom, qui sera le Sol Invictus, le demander à Gala Placidia, comme dans le Canto LXXII:

J'entendis alors

Des voix confuses et des bribes de phrases

Et le chant des oiseaux en contrepoint -

Dans le matin d'été et dans l'aigre refrain

D’une voix si douce:

Moi Placidia, j'ai dormi sous une voûte d'or

Chanson comme les notes d'une corde bien tendue

Mélancolie de femmes, et quelle tendresse, commençais,

Cependant que ... »

39

Cinquante ans et plus après le départ de son Idaho natal, l'homme a été choisi et s'est choisi lui-même pour rendre compte des derniers états d'un cycle méta-historique déjà révolu, et révolu dans sa totalité intemporelle même, pour suivre les affres d'une civilisation s'engouffrant, agonisante, dans les souterrains métapsychiques, dans les "souterrains indiens" de la phase finale de son devenir obligé et de ses plus occultes enfers, le '"vieil oncle Ezra", l'ancien proscrit du collège d'Indiana, gardait encore, parfaitement intact, et quelle plus admirable preuve matérielle de son enracinement transcendantal dans le mystère pélasgien de la « terre des origines », l'accent et le parler de l'Idaho forestier, sauvage et chaotique, de l'Idaho magique et si puissamment magicien de son adolescence illuminée: à l'intérieur de lui-même, dans l'exil de l'exil de son exil, « l'homme sur qui le soleil est descendu » n'a jamais quitté les forêts de noirs sapin sous la brume, les rochers éclatés, les clairières pleines de silence, d'ombres indigo et de neige de ses Montagnes Rocheuses.

Si le parler américain d'Ezra Pound charriait des résonances, produisait une diction, des cadences et un souffle intérieur extrêmement différent - et lointains - de l'américain tel qu'on le parle aujourd'hui, c'est qu'en quittant les rives empoisonnées de la Snake, homme sur le soleil est descendu avait emporté avec lui ce que Donald Hall, en commentant les émissions de celui-ci à la radio - des lectures de ses Cantos - appelait « l'ancien accent américain ». Et le critique G.S Fraser, en évoquant, lui aussi, l'américain personnel d'Ezra Pound: « c'est l’Idaho de 1880 qui, mystérieusement, nous parle ».

Car ce n'est pas Ezra Pound qui a quitté les Etats-Unis, ce sont les Etats-Unis qui se sont à jamais quittés eux-mêmes à travers l'exil d'Ezra Pound, à travers l'exil planétaire et métacosmique, à travers l'exil ontologique de cet exil désormais s'accomplissant sans fin, sans espoir ni merci dans l'exil de son propre exil.

The world o'ershadowed, soiled and overcast,

Void of all joy and full of ire and sadness.

40

Mais comment la dit-il, dans son LXXVII Canto Pisan, comment la dit-il sa très nuptiale vision de l'Italie, de l'Italie Secrète ? Il dit que la brume recouvre les seins de Telus-Helena et remonte l'Arno.

Et s'est-on vraiment demandé - ne fut-ce qu'entre nous autres - pour quelle raison Ezra Pound avait fait de l'Italie - bien au-delà de tout choix politique - sa fulgurante patrie intérieure, sa patrie prophétique et amoureuse, la patrie secrète de son espérance et de son salut, la patrie, aussi, de sa foi perdue et de son grand amour perdu, la patrie ardente de la secretissima ? Je dis qu'une certaine lumière - songerions-nous à la Toscane, à l'Ombrie - pourra bien répondre à cette interrogation, et le faire silencieusement, comme de par sa seule présence-là. Nous approchons du rebord des confessions ultimes, face au vide, face à l'azur, face à la mer écumante et sombre, face à la mort en pleine lumière. Je le sais, la secretissima était une lumière, à midi.

La mer n'est pas plus claire dans l'azur

Ni les Héliades porteurs de lumière

écrit-il dans son sublime LLXXIX Canto Pisan, le grand chant des lynx et du mystère solaire du lynx et des roses, sous l’irradiation embrasante du feu vivant de la grenade, sous la protection des vignes, la protection la plus ancienne. Et la nôtre aussi, car nous le connaissons, nous autres, le Seigneur du Fruit de la Vigne.

Cythèrée, voici des lynx

Le chêne nain va-t-il se couvrir de fleurs ?

Il y a une vigne rose dans ces broussailles

Rouge ? Blanche ? Non, mais une couleur entre les deux

Quand la grenade est ouverte et qu'un rayon de lumière

La pénètre à demi

écrit-il, toujours dans le Canto LXXIX, où il dira aussi, brûlé par le secret rougeoyant de Pomone:

Ce fruit est rempli de feu

Pomone, Pomone

Il n'y a pas de verre plus clair

Que les globes de cette flamme

Quelle mer est plus claire que

Ce corps de grenade

Tenant la flamme ?

Pomone, Pomone

Lynx, garde bien ce verger

Qui a pour nom Mel grana

Ou le champ de Grenade

La traduction française de ces fragments des Cantos Pisanos appartient à Denis Roche (l’Herne, 1965)

Ce qu'Ezra Pound, l'homme sur qui le soleil est descendu, cherchait en Italie, on l'a compris, c'est le Paradis. Toscane, Ombrie, Ezra Pound avait accédé à la certitude inspirée, initiatique, abyssale, que le Paradis était descendu, en Italie, pendant le haut moyen-âge, et que très occultement, il s'y trouvait encore. Pour en trouver la passe interdite, il suffisait de se laisser conduire en avant, aveuglément - et nuptiale ment aveuglé - par la secretissima, par une certaine lumière italienne de toujours.

Jean Parvulesco

(Extrait du Cahier Jean Parvulesco publié en novembre 1989, aux éditions des Nouvelles Littératures Européennes, sous la direction d’André Murcie et Luc-Olivier d’Algange.)

Exposé au milieu du camp, ses compatriotes - ses soi-disant compatriotes - l'avaient enfermé, seul, dans une « cage à gorille » en poutrelles métalliques, entièrement à l'air libre et sans toit, en plein hiver et la nuit un projecteur aveuglant - à dessein - braqué en permanence sur lui. Ce fut ainsi.

Exposé au milieu du camp, ses compatriotes - ses soi-disant compatriotes - l'avaient enfermé, seul, dans une « cage à gorille » en poutrelles métalliques, entièrement à l'air libre et sans toit, en plein hiver et la nuit un projecteur aveuglant - à dessein - braqué en permanence sur lui. Ce fut ainsi.

Enfin, chose également à ne pas passer sous silence, la poésie vivante et agissante des Cantos Pisanos n'est pas seulement à proposer l'institution accélérée de l'Arche Métasymbolique de nos temps voués à l'auto-anéantissement, elle est elle-même, ontologiquement - et de par elle-même, révolutionnairement - cette Arche Métasymbolique.

Enfin, chose également à ne pas passer sous silence, la poésie vivante et agissante des Cantos Pisanos n'est pas seulement à proposer l'institution accélérée de l'Arche Métasymbolique de nos temps voués à l'auto-anéantissement, elle est elle-même, ontologiquement - et de par elle-même, révolutionnairement - cette Arche Métasymbolique.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les Cantos sont, dans l'histoire de la poésie mondiale, un événement unique. Rien n'y ressemble de près ou de loin. Tout au plus pouvons-nous laisser se réverbérer en nous, à son propos, les ors fluants de la prosodie virgilienne, un art odysséen de la navigation, et le dessein récapitulatif et prophétique de La Divine Comédie. L'œuvre ne choisit pas entre l'amplitude et l'intensité, entre l'horizontalité et la verticalité. La vastitude des Cantos loge des formes brèves, des aphorismes qui s'ouvrent allusivement sur d'autres vastitudes. Pound est, avec Saint-John Perse, l'un des très-rares poètes modernes à ne point dédaigner ni le réel, ni le mythe. Les hommes dans le poème de Pound tracent les figures de leurs destinées entre les choses et les dieux. De surprenantes collisions s'opèrent, les temporalités se rencontrent et se traversent selon leurs propriétés et selon leurs signes.

Les Cantos sont, dans l'histoire de la poésie mondiale, un événement unique. Rien n'y ressemble de près ou de loin. Tout au plus pouvons-nous laisser se réverbérer en nous, à son propos, les ors fluants de la prosodie virgilienne, un art odysséen de la navigation, et le dessein récapitulatif et prophétique de La Divine Comédie. L'œuvre ne choisit pas entre l'amplitude et l'intensité, entre l'horizontalité et la verticalité. La vastitude des Cantos loge des formes brèves, des aphorismes qui s'ouvrent allusivement sur d'autres vastitudes. Pound est, avec Saint-John Perse, l'un des très-rares poètes modernes à ne point dédaigner ni le réel, ni le mythe. Les hommes dans le poème de Pound tracent les figures de leurs destinées entre les choses et les dieux. De surprenantes collisions s'opèrent, les temporalités se rencontrent et se traversent selon leurs propriétés et selon leurs signes.

Pound exige beaucoup de son lecteur, c'est sa façon de l'honorer, de le considérer comme son égal. Il est impossible de lire les Cantos sans parcourir les espaces, les savoirs, les songes qu'Ezra Pound lui-même parcourut pour les écrire. Les Cantos sont, à cet égard, une prodigieuse mise en demeure. Ils nous somment de vaincre notre paresse et notre ignorance. Ces chants sont des passerelles entre des mondes qu'il nous faut élever hors de l'oubli par l'attention et la remémoration. Le confucianisme de Pound est ainsi une méditation sur la Mesure qui unit le Ciel et la Terre, les configurations célestes, que traversent les formations ailées des vocables et les événements de l'histoire du monde.

Pound exige beaucoup de son lecteur, c'est sa façon de l'honorer, de le considérer comme son égal. Il est impossible de lire les Cantos sans parcourir les espaces, les savoirs, les songes qu'Ezra Pound lui-même parcourut pour les écrire. Les Cantos sont, à cet égard, une prodigieuse mise en demeure. Ils nous somment de vaincre notre paresse et notre ignorance. Ces chants sont des passerelles entre des mondes qu'il nous faut élever hors de l'oubli par l'attention et la remémoration. Le confucianisme de Pound est ainsi une méditation sur la Mesure qui unit le Ciel et la Terre, les configurations célestes, que traversent les formations ailées des vocables et les événements de l'histoire du monde.

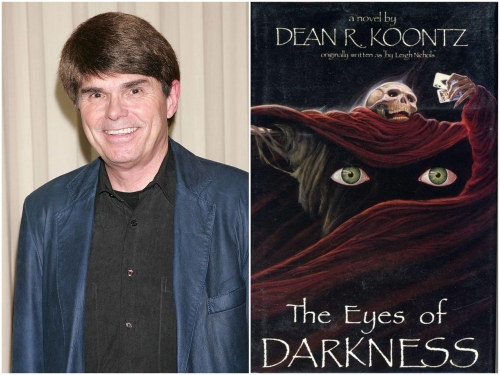

Et voici l'histoire de "The Killer". Le personnage principal est Albert Brock, un patient placé en clinique, qui souffre dans la technosphère, ce qui le prive de paix et de joie. Les bracelets radio (radio au poignet), les maisons parlantes, la télévision, le bruit des voitures, la publicité intrusive, la musique assourdissante ne permettent pas à une personne d'être seule avec elle-même. Les autorités le tiennent en laisse en l'appelant au téléphone. Ce n'est pas encore un téléphone portable, mais un appareil qui est toujours avec Brock, dans une voiture équipée d'une radio :

Et voici l'histoire de "The Killer". Le personnage principal est Albert Brock, un patient placé en clinique, qui souffre dans la technosphère, ce qui le prive de paix et de joie. Les bracelets radio (radio au poignet), les maisons parlantes, la télévision, le bruit des voitures, la publicité intrusive, la musique assourdissante ne permettent pas à une personne d'être seule avec elle-même. Les autorités le tiennent en laisse en l'appelant au téléphone. Ce n'est pas encore un téléphone portable, mais un appareil qui est toujours avec Brock, dans une voiture équipée d'une radio :

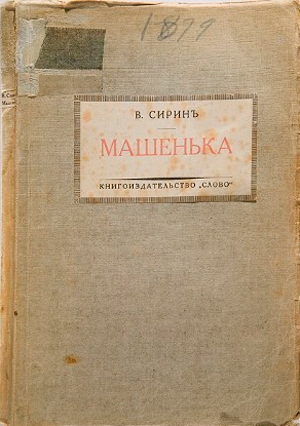

His first Russian literary publications, signed with pseudonym Syrin (the name of the mythological paradise bird), were printed by emigrant press (“Mashenka”, “The Defence”). Some short stories and lyrical poems where he depicted the drama and tragedy of the Russian refugees, the downfall of their first hopes and their despair (an emigrant chess-player Luzhin in “The Defence” committed a suicide by jumping out of the window) were accepted with understanding by readers. One of them was Ivan Bunin, the Noble Prize winner for literature and one of Nabokov’s authorities of that time.

His first Russian literary publications, signed with pseudonym Syrin (the name of the mythological paradise bird), were printed by emigrant press (“Mashenka”, “The Defence”). Some short stories and lyrical poems where he depicted the drama and tragedy of the Russian refugees, the downfall of their first hopes and their despair (an emigrant chess-player Luzhin in “The Defence” committed a suicide by jumping out of the window) were accepted with understanding by readers. One of them was Ivan Bunin, the Noble Prize winner for literature and one of Nabokov’s authorities of that time. “The Gift” ’s author doesn’t say many words about his favorite writers in a direct way. You just see their reflections or allusions to their aesthetics, feel their invisible breathing. At the same time he dedicates the whole chapter 4 to the biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskiy, a famous revolutionary-populist (narodnik) and a spiritual father in the person of Lenin that becomes the negative center of the novel. Nabokov follows the example of Dostoevskiy’s “Demons” and gives a caricature portrait of the revolutionary, but he makes it in a different manner. Not to be boring, Nabokov retells the Cherdyntsev’s utilitarian and socially limited ideas in the black ironic verse.

“The Gift” ’s author doesn’t say many words about his favorite writers in a direct way. You just see their reflections or allusions to their aesthetics, feel their invisible breathing. At the same time he dedicates the whole chapter 4 to the biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskiy, a famous revolutionary-populist (narodnik) and a spiritual father in the person of Lenin that becomes the negative center of the novel. Nabokov follows the example of Dostoevskiy’s “Demons” and gives a caricature portrait of the revolutionary, but he makes it in a different manner. Not to be boring, Nabokov retells the Cherdyntsev’s utilitarian and socially limited ideas in the black ironic verse. He finished the book of memories – its first title “Conclusive Evidence” (1951) – later changed into “Speak, Memory” by the author -, where he described in a pure classic manner his happy childhood in a family village Rozhdestveno near St. Petersburgh, portrayed with infinite tender his parents and represented the general life atmosphere of a good old pre-revolutionary Russia.

He finished the book of memories – its first title “Conclusive Evidence” (1951) – later changed into “Speak, Memory” by the author -, where he described in a pure classic manner his happy childhood in a family village Rozhdestveno near St. Petersburgh, portrayed with infinite tender his parents and represented the general life atmosphere of a good old pre-revolutionary Russia. Nabokov tried to defend himself. He said that “Lolita” couldn’t be considered as anti-American. While composing the story, he tried to be an American writer. What one should bear in mind he was not a realistic author, he wrote fiction. It had taken Nabokov some forty years to invent Russia and Western Europe. And at that moment he faced the task of inventing America. He didn’t like Humbert Humbert. Indeed that character was not an American citizen, he was a foreigner and an anarchist. Nabokov disagreed with him in many ways, besides, nymphets like his, disagreed, for example, with Freid or Marx.

Nabokov tried to defend himself. He said that “Lolita” couldn’t be considered as anti-American. While composing the story, he tried to be an American writer. What one should bear in mind he was not a realistic author, he wrote fiction. It had taken Nabokov some forty years to invent Russia and Western Europe. And at that moment he faced the task of inventing America. He didn’t like Humbert Humbert. Indeed that character was not an American citizen, he was a foreigner and an anarchist. Nabokov disagreed with him in many ways, besides, nymphets like his, disagreed, for example, with Freid or Marx. Nabokov’s critical biography by Nikolai Gogol (a non-Christian interpretation of a Christian author were the first books, published in the Soviet Union. But his “Lectures on Russian Literature”, “Lecture on Literature” (on Western Europe), “Strong Opinions” where he collected some interviews, letters and articles were unknown until post-soviet times.

Nabokov’s critical biography by Nikolai Gogol (a non-Christian interpretation of a Christian author were the first books, published in the Soviet Union. But his “Lectures on Russian Literature”, “Lecture on Literature” (on Western Europe), “Strong Opinions” where he collected some interviews, letters and articles were unknown until post-soviet times.

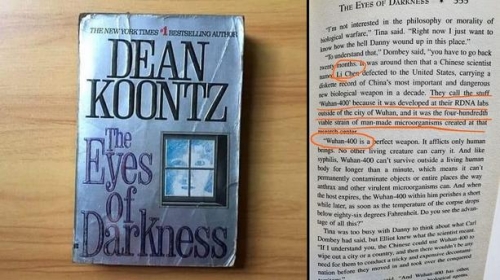

La Chine accuse les États-Unis ! Nous avions déjà la crise sanitaire et la crise économique, voici peut-être une nouvelle crise diplomatique majeure puisqu’un porte-parole du ministère chinois des Affaires étrangères suggère que l’épidémie n’est pas nécessairement accidentelle…et qu’elle provient d’Amérique !

La Chine accuse les États-Unis ! Nous avions déjà la crise sanitaire et la crise économique, voici peut-être une nouvelle crise diplomatique majeure puisqu’un porte-parole du ministère chinois des Affaires étrangères suggère que l’épidémie n’est pas nécessairement accidentelle…et qu’elle provient d’Amérique !

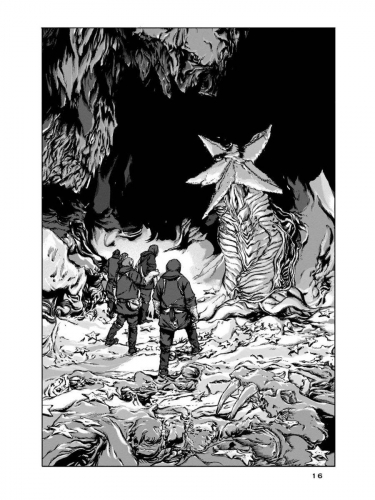

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

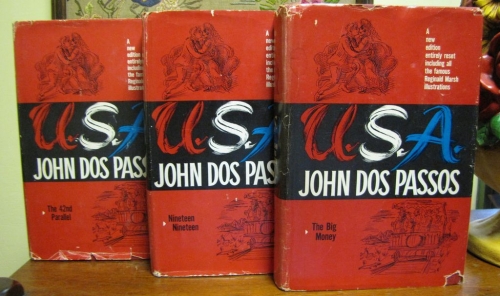

It may be Nock’s “

It may be Nock’s “

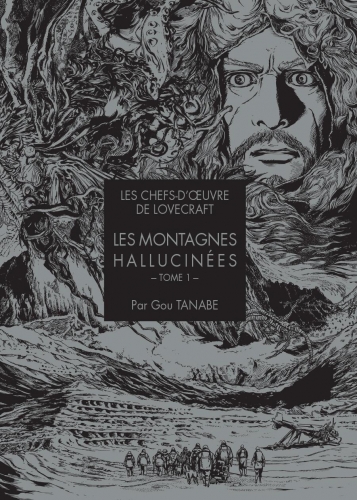

Mais avant cela, il faut tout d’abord revenir sur quelques caractéristiques majeurs, ainsi que quelques grands thèmes présents,pour ne pas dire constitutifs, de l’œuvre de Lovecraft. Évidemment il y a tout d’abord ces entités primordiales monstrueuses, ces abominations répondant aux noms de Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep ou bien encore Cthulhu. A l’instar de nombreux éléments qui façonnent l’univers de l’auteur, son panthéon noir est sujet à l’intertextualité : le lecteur retrouvera ces monstruosités dans divers nouvelles indépendantes des unes des autres. Ces horreurs sont également citées dans des livres, le plus souvent des vieux grimoires comme le Necronomicon, les Manuscrits Pnakotiques, l’Unaussprechlichen Kulten,etc, eux-aussi présents dans la plupart des écrits de Lovecraft (et il en est de même pour certains lieux, bien réels ou imaginaires). L’intertextualité constitue une véritable toile de fond qui contribue à la création de l’univers « lovecraftien ».

Mais avant cela, il faut tout d’abord revenir sur quelques caractéristiques majeurs, ainsi que quelques grands thèmes présents,pour ne pas dire constitutifs, de l’œuvre de Lovecraft. Évidemment il y a tout d’abord ces entités primordiales monstrueuses, ces abominations répondant aux noms de Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep ou bien encore Cthulhu. A l’instar de nombreux éléments qui façonnent l’univers de l’auteur, son panthéon noir est sujet à l’intertextualité : le lecteur retrouvera ces monstruosités dans divers nouvelles indépendantes des unes des autres. Ces horreurs sont également citées dans des livres, le plus souvent des vieux grimoires comme le Necronomicon, les Manuscrits Pnakotiques, l’Unaussprechlichen Kulten,etc, eux-aussi présents dans la plupart des écrits de Lovecraft (et il en est de même pour certains lieux, bien réels ou imaginaires). L’intertextualité constitue une véritable toile de fond qui contribue à la création de l’univers « lovecraftien ». Cette dialectique s’accompagne ainsi d’une atmosphère anti-moderne palpable, voir d’un véritable retour à l’archaïque (type de sculptures, d’architectures, de sociétés humaines, etc). Mais, encore une fois, H.P.Lovecraft pouvait également s’intéresser à des « tendances » de son époque, comme l’eugénisme. Certes Lovecraft était raciste et antisémite – les pseudo-journalistes et autres écrivaillons n’oublient jamais de gloser là-dessus bien évidemment – mais c’est surtout la dégénérescence atavique qui est intéressant chez lui. Les nouvelles La peur qui rode et surtout Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth mettent horriblement en avant ces thèmes, voir aussi celui du Destin.

Cette dialectique s’accompagne ainsi d’une atmosphère anti-moderne palpable, voir d’un véritable retour à l’archaïque (type de sculptures, d’architectures, de sociétés humaines, etc). Mais, encore une fois, H.P.Lovecraft pouvait également s’intéresser à des « tendances » de son époque, comme l’eugénisme. Certes Lovecraft était raciste et antisémite – les pseudo-journalistes et autres écrivaillons n’oublient jamais de gloser là-dessus bien évidemment – mais c’est surtout la dégénérescence atavique qui est intéressant chez lui. Les nouvelles La peur qui rode et surtout Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth mettent horriblement en avant ces thèmes, voir aussi celui du Destin. En 1930, une expédition en Antarctique est organisée par l’Université Miskatonic. Celle-ci est composée de nombreux scientifiques et d’étudiants : biologistes, géologues, et physiciens. Ayant établi leur QG sur le mont Erebus, les premières découvertes ne tardent pas à voir le jour. Enthousiasmé, le Professeur Lake décide de poursuivre les recherches au nord-ouest. C’est en arrivant sur place qu’ils vont découvrir une chaîne de montagnes plus haute encore que l’Himalaya. Une fois leur camp installé, l’équipe met à jour une grotte abritant des restes de créatures inconnues, mi-animales, mi-végétales, que le Pr. Lake baptisera « les Anciens », en référence à la description de créatures semblables dans le Necronomicon. Une violente tempête s’abat sur la région et le contact entre les deux équipes est coupée. Le Professeur Dyer décide d’aller aider ses confrères partis au nord-ouest. Sur place, ils ne trouveront que les cadavres horriblement mutilés de l’équipe et des chiens de traîneau. Seul manque à l’appel Gedney, l’assistant de Lake, et un chien…

En 1930, une expédition en Antarctique est organisée par l’Université Miskatonic. Celle-ci est composée de nombreux scientifiques et d’étudiants : biologistes, géologues, et physiciens. Ayant établi leur QG sur le mont Erebus, les premières découvertes ne tardent pas à voir le jour. Enthousiasmé, le Professeur Lake décide de poursuivre les recherches au nord-ouest. C’est en arrivant sur place qu’ils vont découvrir une chaîne de montagnes plus haute encore que l’Himalaya. Une fois leur camp installé, l’équipe met à jour une grotte abritant des restes de créatures inconnues, mi-animales, mi-végétales, que le Pr. Lake baptisera « les Anciens », en référence à la description de créatures semblables dans le Necronomicon. Une violente tempête s’abat sur la région et le contact entre les deux équipes est coupée. Le Professeur Dyer décide d’aller aider ses confrères partis au nord-ouest. Sur place, ils ne trouveront que les cadavres horriblement mutilés de l’équipe et des chiens de traîneau. Seul manque à l’appel Gedney, l’assistant de Lake, et un chien…

Guide to Kulchur is unique in both its structure and style. Written in Pound’s folksy demotic English that at times seems more akin to Mark Twain or Joel Chandler Harris, the book is arranged in a series of very short chapters that seem to unfold in a haphazard fashion. The book’s form only becomes manifest the longer one reads, and by the end of the book one is amazed at how Pound has managed to weave seamlessly the many strands of Western and ancient Chinese thought.

Guide to Kulchur is unique in both its structure and style. Written in Pound’s folksy demotic English that at times seems more akin to Mark Twain or Joel Chandler Harris, the book is arranged in a series of very short chapters that seem to unfold in a haphazard fashion. The book’s form only becomes manifest the longer one reads, and by the end of the book one is amazed at how Pound has managed to weave seamlessly the many strands of Western and ancient Chinese thought.

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”